Over 2 million + professionals use CFI to learn accounting, financial analysis, modeling and more. Unlock the essentials of corporate finance with our free resources and get an exclusive sneak peek at the first chapter of each course. Start Free

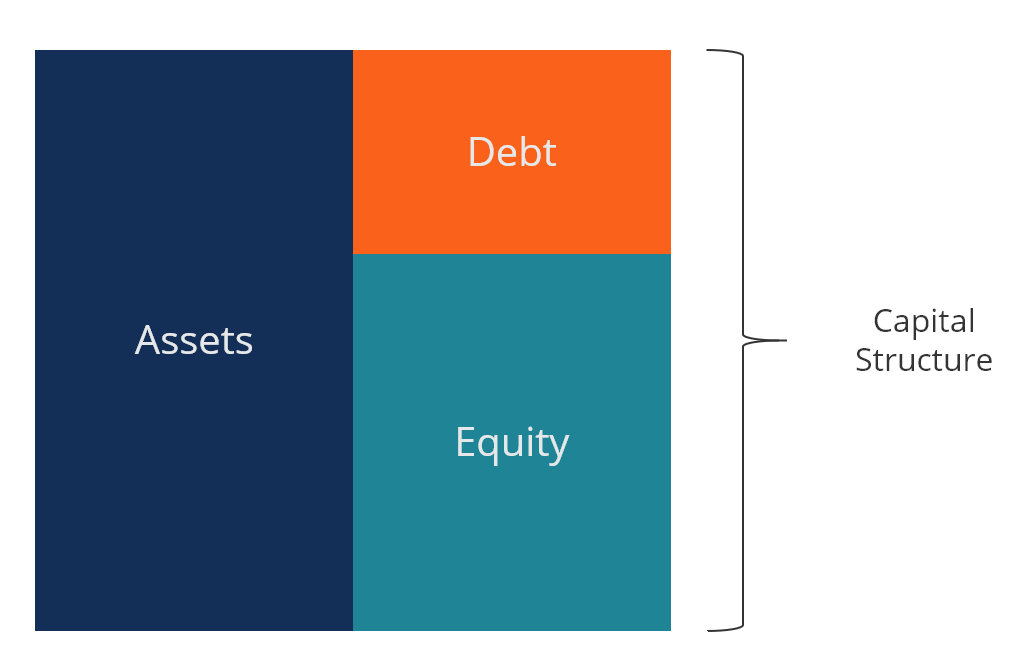

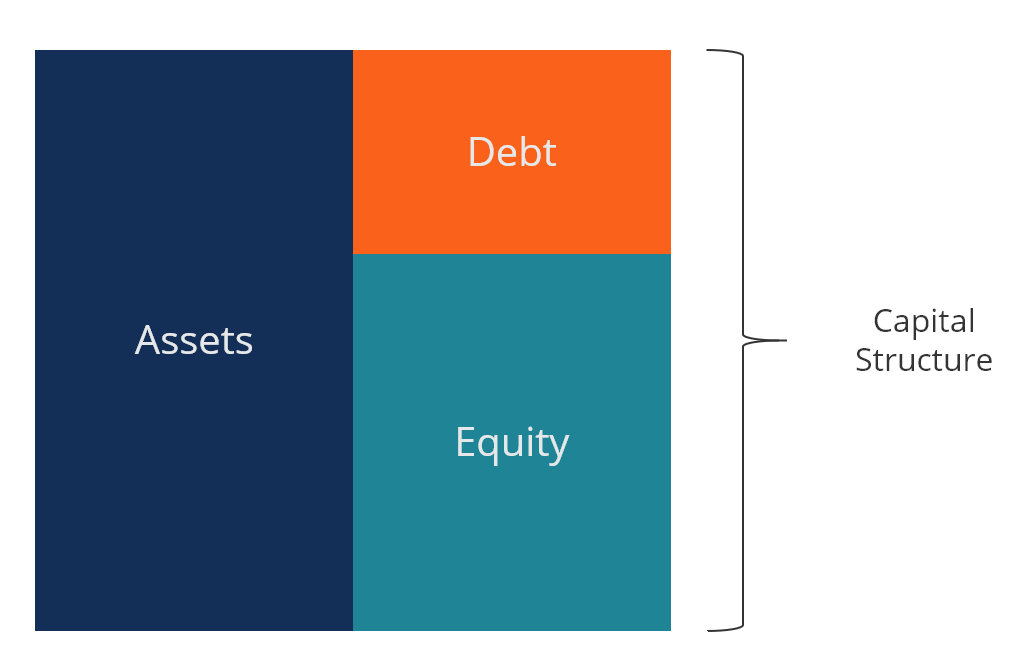

Capital structure refers to the amount of debt and/or equity employed by a firm to fund its operations and finance its assets. A firm’s capital structure is typically expressed as a debt-to-equity or debt-to-capital ratio.

Debt and equity capital are used to fund a business’s operations, capital expenditures, acquisitions, and other investments. There are tradeoffs firms have to make when they decide whether to use debt or equity to finance operations, and managers will balance the two to find the optimal capital structure.

The optimal capital structure of a firm is often defined as the proportion of debt and equity that results in the lowest weighted average cost of capital (WACC) for the firm. This technical definition is not always used in practice, and firms often have a strategic or philosophical view of what the ideal structure should be.

In order to optimize the structure, a firm can issue either more debt or equity. The new capital that’s acquired may be used to invest in new assets or may be used to repurchase debt/equity that’s currently outstanding, as a form of recapitalization.

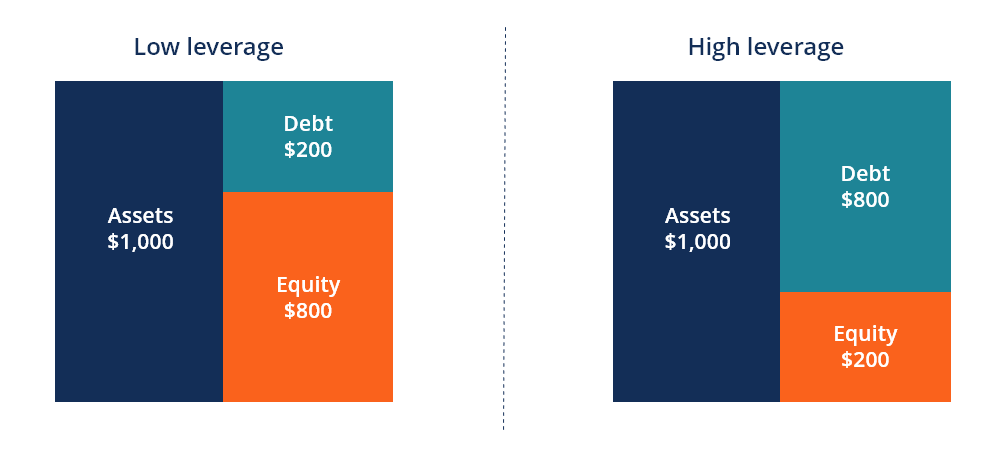

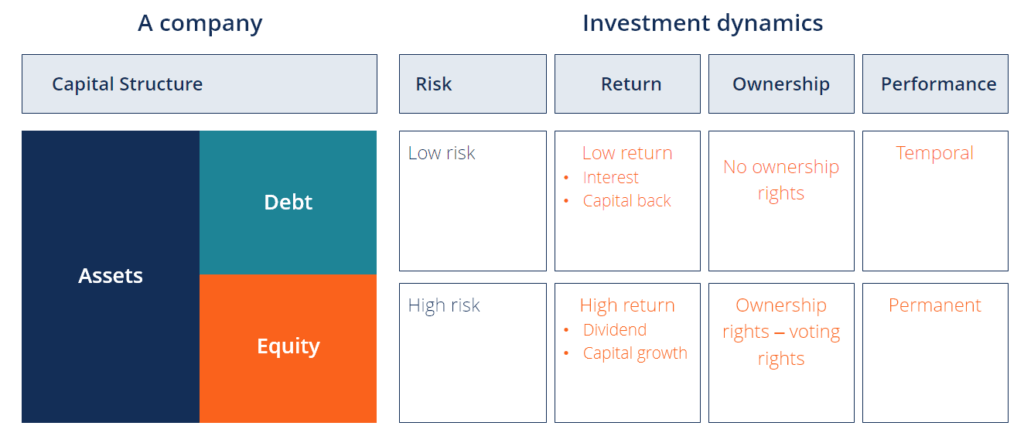

Below is an illustration of the dynamics between debt and equity from the view of investors and the firm.

Debt investors take less risk because they have the first claim on the assets of the business in the event of bankruptcy. For this reason, they accept a lower rate of return and, thus, the firm has a lower cost of capital when it issues debt compared to equity.

Equity investors take more risk, as they only receive the residual value after debt investors have been repaid. In exchange for this risk, investors expect a higher rate of return and, therefore, the implied cost of equity is greater than that of debt.

A firm’s total cost of capital is a weighted average of the cost of equity and the cost of debt, known as the weighted average cost of capital (WACC).

The formula is equal to:

WACC = (E/V x Re) + ((D/V x Rd) x (1 – T))

E = market value of the firm’s equity (market cap)

D = market value of the firm’s debt

V = total value of capital (equity plus debt)

E/V = percentage of capital that is equity

D/V = percentage of capital that is debt

Re = cost of equity (required rate of return)

Rd = cost of debt (yield to maturity on existing debt)

T = tax rate

Capital structures can vary significantly by industry. Cyclical industries like mining are often not suitable for debt, as their cash flow profiles can be unpredictable and there is too much uncertainty about their ability to repay the debt.

Other industries, like banking and insurance, use huge amounts of leverage, and their business models require large amounts of debt.

Private companies may have a harder time using debt over equity, particularly small businesses, which are required to have personal guarantees from their owners.

A firm that decides it should optimize its capital structure by changing the mix of debt and equity has a few options to effect this change.

Each of these three methods can be an effective way of recapitalizing the business.

In the first approach, the firm borrows money by issuing debt and then uses all of the capital to repurchase shares from its equity investors. This has the effect of increasing the amount of debt and decreasing the amount of equity on the balance sheet.

In the second approach, the firm will borrow money (i.e., issue debt) and use that money to pay a one-time special dividend, which has the effect of reducing the value of equity by the value of the divided. This is another method of increasing debt and reducing equity.

In the third approach, the firm moves in the opposite direction and issues equity by selling new shares, then takes the money and uses it to repay debt. Since equity is costlier than debt, this approach is not desirable and often only done when a firm is overleveraged and desperately needs to reduce its debt.

There are many tradeoffs that owners and managers of firms have to consider when determining their capital structure. Below are some of the tradeoffs that should be considered.

When firms execute mergers and acquisitions, the capital structure of the combined entities can often undergo a major change. Their resulting structure will depend on many factors, including the form of the consideration provided to the target (cash vs shares) and whether existing debt for both companies is left in place or not.

For example, if Elephant Inc. decides to acquire Squirrel Co. using its own shares as the form of consideration, it will increase the value of equity capital on its balance sheet. If, however, Elephant Inc. uses cash (which is financed with debt) to acquire Squirrel Co., it will have increased the amount of debt on its balance sheet.

Determining the pro forma capital structure of the combined entity is a major part of M&A financial modeling. The screenshot below shows how two companies are combined and recapitalized to produce an entirely new balance sheet.

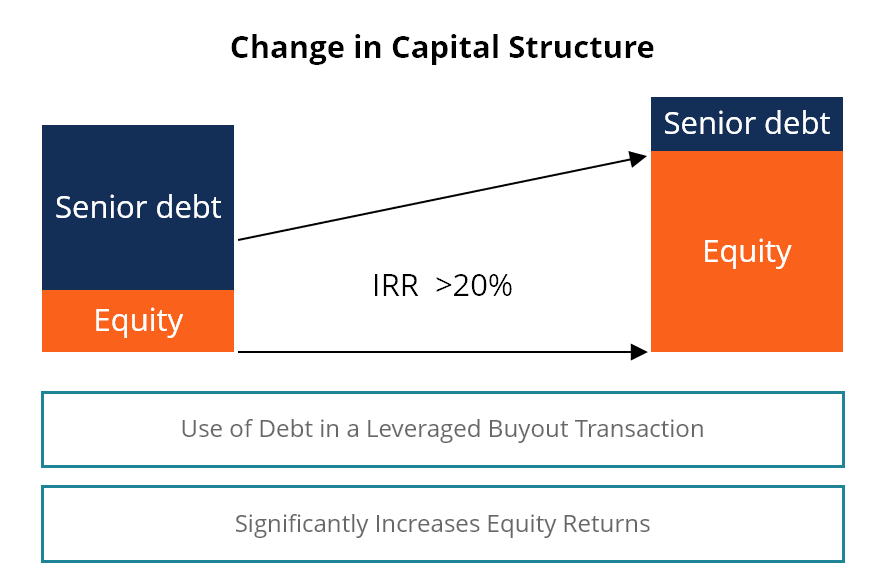

In a leveraged buyout (LBO) transaction, a firm will take on significant leverage to finance the acquisition. This practice is commonly performed by private equity firms seeking to invest the smallest possible amount of equity and finance the balance with borrowed funds.

The image below demonstrates how the use of leverage can significantly increase equity returns as the debt is paid off over time.

Learn more about LBO transactions and why private equity firms often use this strategy.

Thank you for reading this guide and overview of capital structures and the important considerations that owners, managers, and investors have to take into account. To continue learning and advancing your career, these additional CFI resources will be a big help:

Gain in-demand industry knowledge and hands-on practice that will help you stand out from the competition and become a world-class financial analyst.